Tell stories! (Oliver Sacks edition)

Do you ever get tired of me proselytizing on behalf of stories? Well, too bad. I am a story evangelist. And I’m not alone.

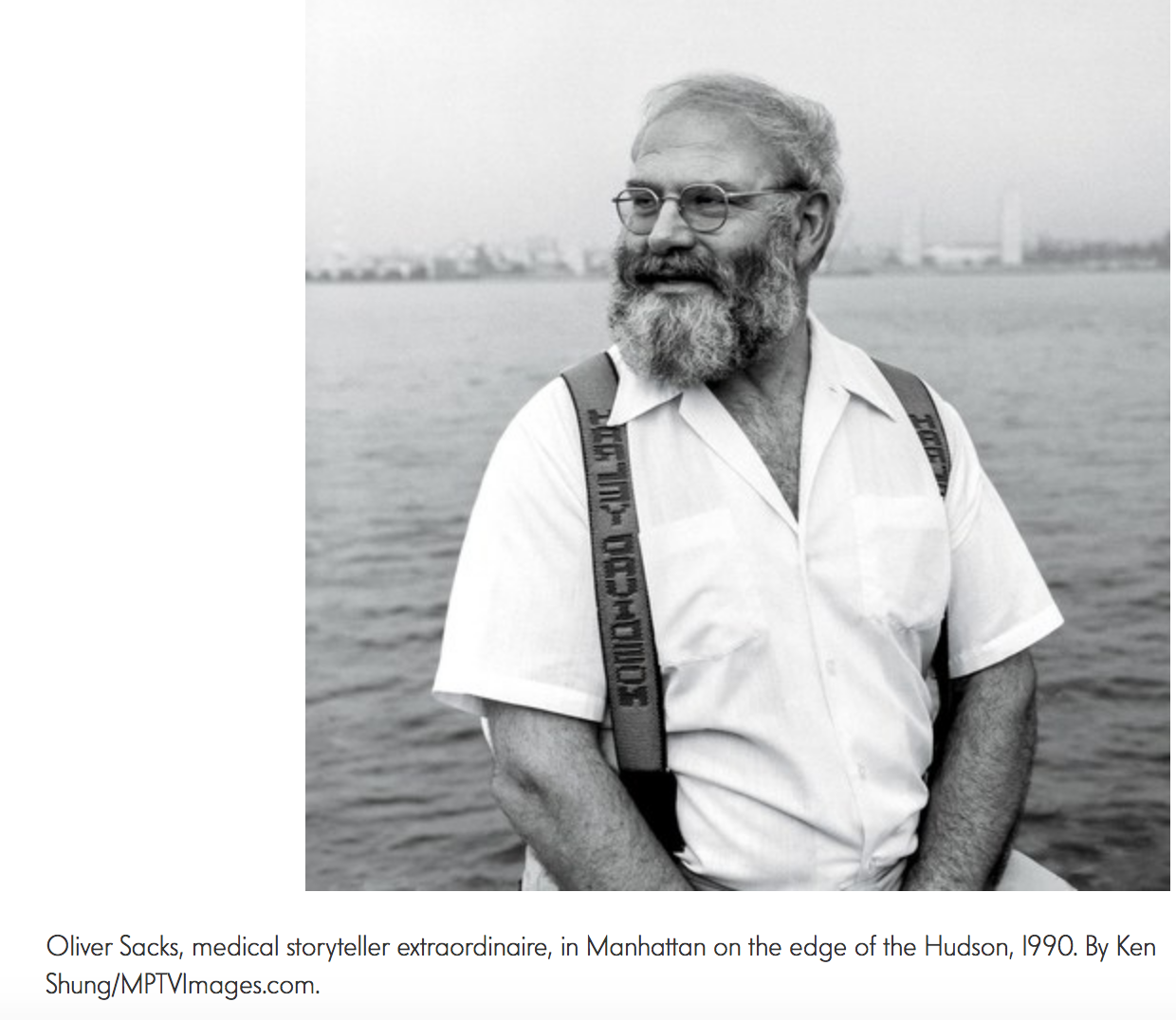

Catching up on a dusty old issue of Vanity Fair, I found a story by Lawrence Wechsler with notes of his conversations with the late neurologist Oliver Sacks.

I’m not a science nerd by any means. But I have been a huge Oliver Sacks fan ever since I read his remarkable book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: and Other Clinical Tales. Many more people know him from his book Awakenings, later turned into a movie starring Robin Williams as a Sacks-like character.

Sacks took his material from real life, from the rich stories he was privy to as he treated patients with a range of puzzling neurological ailments. And the key word in that sentence? Stories.

Stories resonate—and get remembered

Other doctors might have treated the same people and seen them as mere cases. But Sacks recognized them as people—with stories to tell. Stories particular to each patient’s own condition, but with elements that could resonate with all of us.

Here’s what Wechsler writes about one of his conversations with Sacks:

“He respects facts, he tells me, and he has a scientist’s passion for precision. But facts, he insists, must be embedded in stories. Stories—people’s stories—are what really have him hooked…”

As you might guess, I added the emphasis there. Tell facts, by all means. But tell them in a context that will make them memorable.

And recognize that facts by themselves only go so far:

“He recently attended a conference on Tourette’s syndrome. Ninety-two specialists gave papers on EKG readings, electrical conductivity of the brain—all kinds of technical subjects. Sacks, the 93rd, got up and said, ‘It’s strange. I’ve been sitting here all weekend and heard not one sentence on what it might be like to be a Touretter.'”

I can practically see the eminent neurologists in the audience shrinking in their chairs: How could we lose sight of the patients?

Whether you’re conducting scientific research, or turning around companies, or selling vacuums, your work doesn’t exist in (you should pardon the expression) a vacuum. Everything we do touches our fellow human beings in some way, large or small. And that produces stories. And stories connect us to one another.

Tell stories. Every time.