History, small and large — the storytelling of Jimmy Breslin

History documents the major players: kings, presidents. But as feminist historians have reminded us over the last several decades, if you document only the major players, you miss the lives of tens of millions, hundreds of millions of people. It may seem strange to segue from feminist historians to Jimmy Breslin—the brash, gruff, journalistic legend who died this weekend. Breslin was no feminist. But he did have an eye out for the lives of people who often get passed over: the working stiffs.

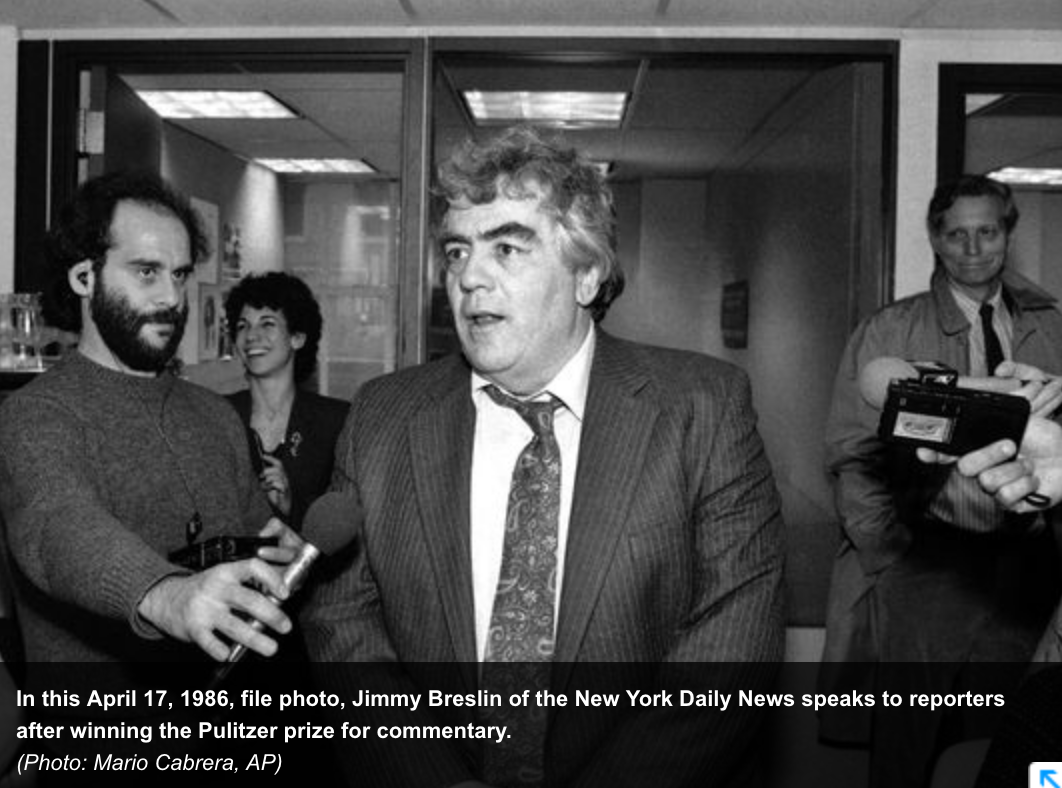

Photo: Mario Cabrera, AP

Looking at the world through the eyes of the people historians and other journalists ignored, Jimmy Breslin saw so much more than world events; he saw stories. If you want to know about the impacts, large and small, that those events had on actual human beings, read Breslin.

Here’s the lede from a story he filed in 1963:

Clifton Pollard was pretty sure he was going to be working on Sunday, so when he woke up at 9 a.m., in his three-room apartment on Corcoran Street, he put on khaki overalls before going into the kitchen for breakfast.

Just two adjectives in that 40-word sentence—three, if you’re going to insist that the hyphenated “three-room” counts as separate words—but you can already see the guy, right? You have a sense of his life. Toward the end of the first paragraph, Pollard’s boss does indeed call him in to work, saying, “I guess know what it’s for.”

And then the second paragraph, presented here in its entirety, delivers the kicker:

He hung up the phone, finished breakfast, and left his apartment so he could spend Sunday digging a grave for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Jimmy Breslin captures details

It seems like Breslin documents every blade of grass around the gravesite.

Leaves covered the grass. When the yellow teeth of the reverse hoe first bit into the ground, the leaves made a threshing sound which could be heard above the motor of the machine. When the bucket came up with its first scoop of dirt, Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, walked over and looked at it.

“That’s nice soil,” Metzler said. “I’d like to save a little of it,” Pollard said. “The machine made some tracks in the grass over here and I’d like to sort of fill them in and get some good grass growing there, I’d like to have everything, you know, nice.”

And then in the second half of the piece, he shows us what became of Pollard’s handiwork. The pivot comes with this sentence:

Yesterday morning, at 11:15, Jacqueline Kennedy started toward the grave.

Breslin seems to observe the events not from the press pool, but from the street:

She walked past silent people who strained to see her and then, seeing her, dropped their heads and put their hands over their eyes.

And when the procession finally arrives at Arlington, back to Clifton Pollard’s territory. He wasn’t at the ceremony, Jimmy Breslin tells us:

Clifton Pollard wasn’t at the funeral. He was over behind the hill, digging graves for $3.01 an hour in another section of the cemetery. He didn’t know who the graves were for. He was just digging them and then covering them with boards.

“They’ll be used,” he said. “We just don’t know when.”

Stories are not about words

It seems safe to say that journalists turned out hundreds of thousands of words about the assassination of America’s handsome president. But only one journalist told us how the earth sounded when they dug his grave. Told us how the guy in the khaki overalls felt “honored” to give up his Sunday for this purpose. Only one journalist took us to the hill behind the gravesite and let us stand there with the “cameramen and writers and soldiers and Secret Service men…saying prayers out loud and choking.”

Jimmy Breslin told stories. Stories are not about words strung together—Breslin understood that better than most. Stories are about details strung together. Details that make events come alive for the reader who can’t get any closer to the action than the words in the paper.

Breslin’s gone now. Who can find the details that make up a great story?

Maybe you?