Reining in language – self-censorship and despotism

Have you seen a short film called Despotism? Unless you were in school in the late 1940s-’50s, probably not.

The people who made this 10-minute film in 1946 lived in a world where despots had until very recently held sway across Europe and Asia. They saw first-hand how despotism could not just destroy countries; it could also destroy individuals. It could break people’s will—often without a single shot being fired.

I want to draw your attention particularly to its discussion of language and self-censorship, which begins at about the 7:00 mark. In a little dramatization, we see teachers being trained:

“This business about open-mindedness is nonsense. It’s a waste of time trying to teach students to think for themselves. It’s our job to tell ’em.”

This leads to its logical conclusion: a student telling his parents, “But it must be true. I saw it in this book right here.”

(A book, in case you’d forgotten, is like the Internet on paper.)

Yes, the boy in the film is the direct ancestor of the folks who ate up the “fake news” Russian-controlled trolls seeded the internet with before our election. Our critical faculties are already degraded, and the despotism hasn’t even taken hold yet.

Censorship and self-censorship

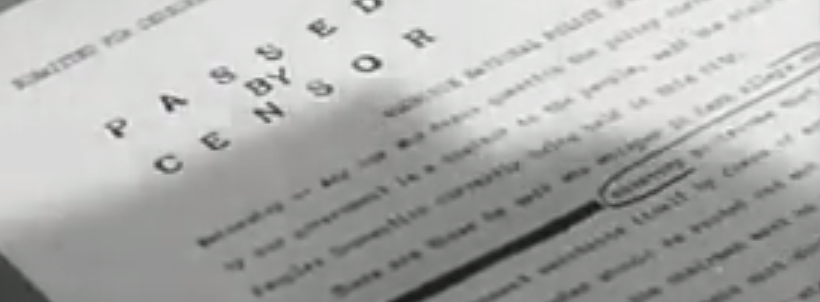

The film shows a bespectacled man editing copy and then stamping it “Passed by Censor.” Chilling, right?

Even more chilling to me is the self-censorship. In the film, we see an editor taken to task by his publication’s “Advertising Manager” (at 8:31):

“I thought I told you to kill that story. It’ll cost us a lot of advertising.”

Now surely no media outlet in 21st century America would make a decision to kill a story based on ad sales—or to run a non-newsworthy story based on ratings. Right?

The editor in the film quits his job rather than compromise his journalistic integrity. A fine man with great principles. Oh, right—I forgot it’s fiction.

Masha Gessen on self-censorship

If you haven’t read Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen’s work on surviving in an autocracy, I highly recommend it.

In much of her work, Gessen reminds us that the state censor merely acts as the final arbiter of what gets published. The first—and usually most thorough—censor remains the writer. Here Gessen describes the process she went through as deputy editor of an independent magazine in Russia:

“This is how self-censorship works. One bargains with oneself. How much can I sacrifice before I lose respect for myself as a journalist? Can I respect myself if I don’t give a story the play it deserves because I’m afraid? Can I respect myself if I kill a story because I’m afraid? Can I respect myself if I force the reader to look for the truth between the lines because I’m afraid?

And does it matter whom I’m afraid of? One can be afraid of the FSB, organized crime, the police. And one can also be afraid of the fears of others—companies who will pull their ads, for example, or investors who will pull their money because they fear the association with a risk-taking publication will cost them dearly.”

Eighty-odd years ago, in his first Inaugural address, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt told the country, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

These days, I think we have a lot more to fear—but “fear itself” may be the most insidious thing. If fear keeps us from writing and publishing honest work, from speaking truth to power, we’re lost.

Unless we save ourselves, I don’t know who else can do it.