Reading speeches vs. winging it, presidential edition

If you see articles about speeches and speechwriting popping up all over your news feed, that can mean only one thing: It’s State of the Union time. Many people hate reading speeches someone else has written. It’s an acquired skill, but smart people know it’s worth acquiring. It’s much easier to read a speech written by a skillful speechwriter than to ad lib at a podium. Especially with the world watching.

I’ve written before about the man who purportedly writes the current president’s speeches. And if he weren’t an unrepentant white supremacist—or as Jon Lovett of Crooked Media calls him, “a C+ Santa Monica fascist”—I might even feel sorry for the dude.

One of the key principles of speechwriting is that you need to match your speaker’s voice—vocabulary, cadence, and content. For most presidential speechwriters, this undoubtedly means raising the bar: Imagine trying to match the brilliance of Bill Clinton’s or Barack Obama’s thinking. I mean, these men are Constitutional scholars, graduates of Ivy League law schools. The current president’s speechwriter only has to match the vocabulary of a second-grader.

But matching your speaker’s voice may only be the second-hardest thing about being a speechwriter. Because before you can write for someone, they have to accept the idea that they need you.

President Obama had written a best-selling book before he hired his first speechwriter. After talking with Jon Favreau, then-Senator Obama said, “You seem like a nice guy, but I don’t need a speechwriter.” Favreau got the job, though. As did many other men and women.

Apparently our current president feels much the same as Senator Obama did. Olivia Nuzzi’s illuminating article in New York magazine—“Who really writes Trump’s speeches? The White House won’t say”—contains this quote, said to come from “multiple sources close to the president”:

“Trump hates the idea that anybody puts words in his mouth. He hates the idea that everything isn’t written by him.”

Reading speeches—and writing them too

I’ve always said that my favorite clients are people who recognize great writing when they see it but are too busy to write it themselves. The current president may have the time to write for himself—if he can tear himself away from Fox News and Twitter long enough—but that’s not why he feels no need for a speechwriter.

Nuzzi eventually got this explanation from the White House:

“…when President Trump communicates with the American people, his words are his own and come directly from his heart. His unparalleled ability to speak to and connect with people from across the country, including those who have felt forgotten by Washington for many years, will never waver.”

This fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of having a speechwriter. A good speechwriter will never put words in your mouth that are not already in your “heart.” A good speechwriter finds out what’s in your heart—either because she’s worked long enough with you to know what you’re thinking before you think it, or because you take the time to talk with her before she starts work and then you read and comment on the drafts.

Bill Clinton, June Shih, and the Little Rock Nine

Last September, the Clinton Presidential Library published drafts of his address at the 40th anniversary of the integration of Little Rock’s Central High School by the “Little Rock Nine.” Comparing a draft by June Shih—one of the few women to rise to the level of presidential speechwriter—with the final draft, you can see the care that President Clinton took to personalize the remarks.

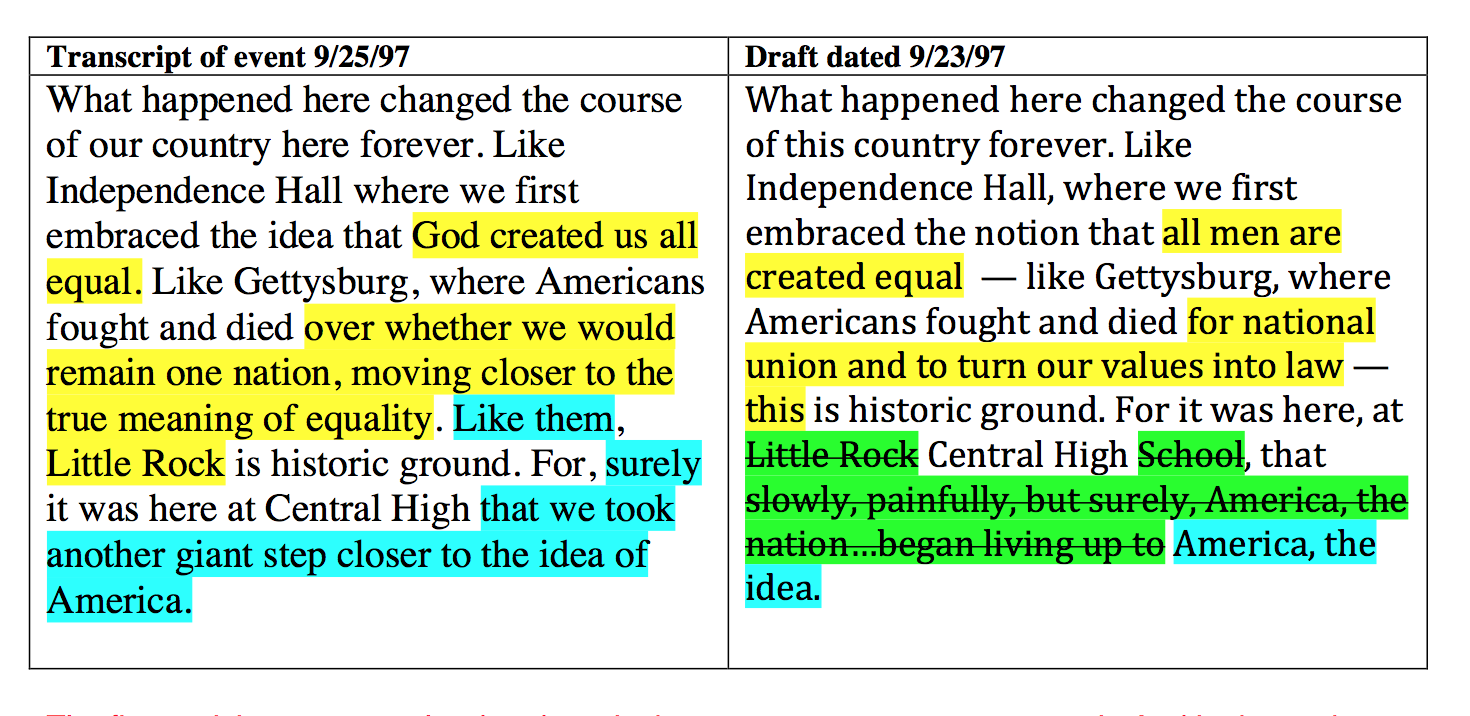

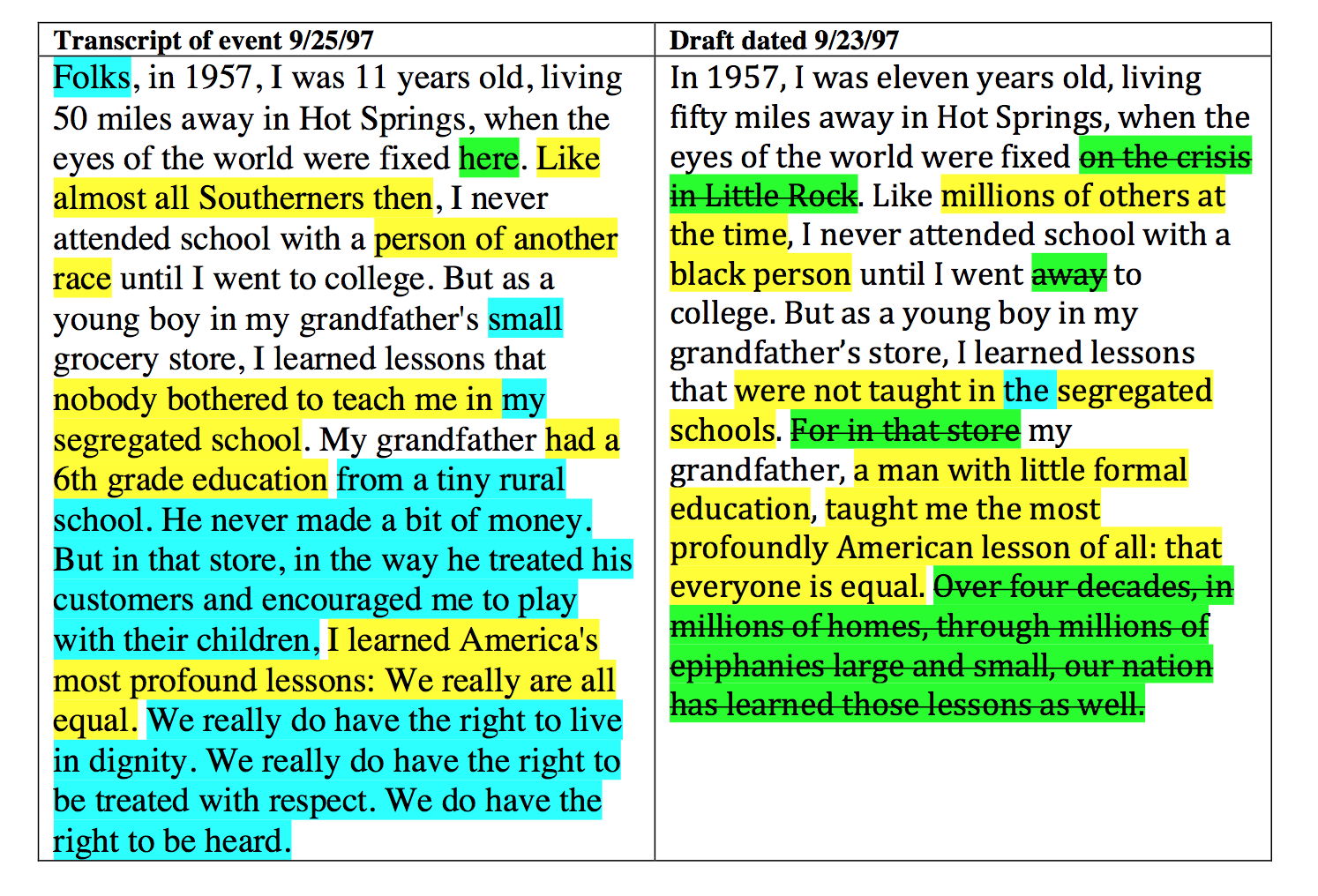

I analyzed these drafts side-by-side for the critical reading program I put together for my writers, but you can see the originals at the Clinton library site. Yellow marks material that got reworked between the early draft (on the right) and the final. The green highlights material that was deleted before the final draft; and the blue are straight additions to the final draft.

Generally these make the language tighter, more concise. But sometimes, they’re the president adding personal details. The speechwriter sketched the outlines of some of these details in the earlier draft, but the president drills down on them in ways that make the stories indelible. That’s how the collaboration between writer and speaker is supposed to work.

Generally these make the language tighter, more concise. But sometimes, they’re the president adding personal details. The speechwriter sketched the outlines of some of these details in the earlier draft, but the president drills down on them in ways that make the stories indelible. That’s how the collaboration between writer and speaker is supposed to work.

When you should you use a speechwriter?

Look, all of us have the ability to speak on our own. We do it every day. Still, just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should.

If you’re speaking on a larger platform that usual—if your words will reach people beyond the folks sitting in front of you in the audience: Use a speechwriter.

If you have specific expertise in a certain area and that’s the area you’re asked to speak about: Go for it. But make sure you sketch out the speech so you don’t start to ramble.

If you’re expected to have specific expertise in a number of areas and you don’t have time to keep up with all of them (if, for instance, you’re the freaking president of the United States): Don’t be an idiot. Use a speechwriter.

If when you’re reading speeches, you sound like you’re reading speeches: Get yourself a speech coach and/or spend some time rehearsing. All the best speakers do.

If you’d like a full copy of my analysis of Bill Clinton and June Shih’s Little Rock Nine speech, just tell me where to send it.