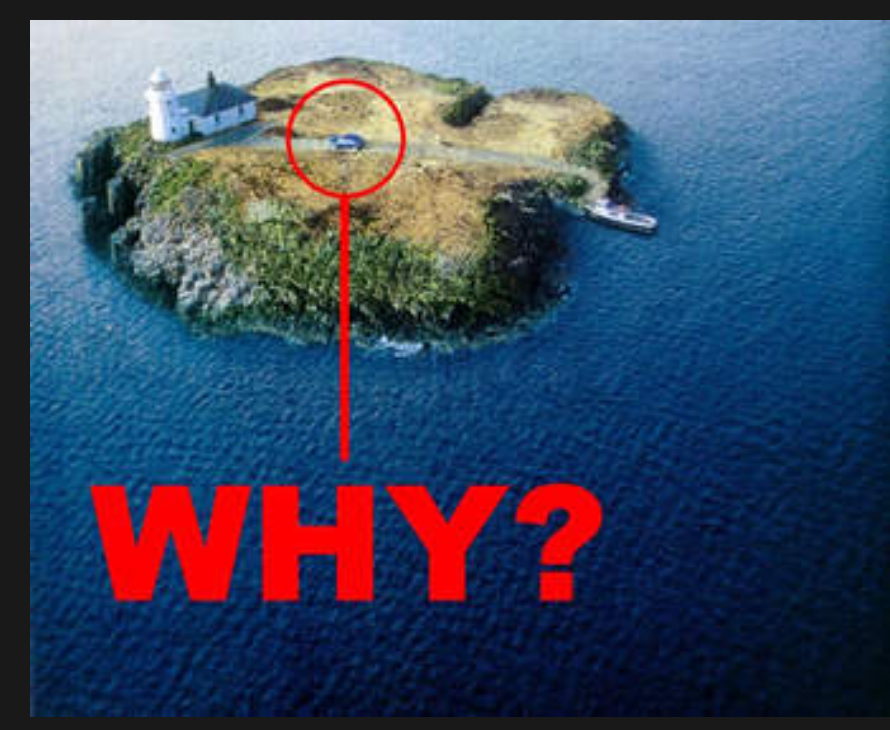

Why? One of the most powerful words

“Why?” may be one of the most powerful words in our language. Maybe that’s why toddlers go on endless jags of inquiry. Have you ever tried to answer “Why is the sky blue?”

It’s endearing at first—when you know the answers. But if the string of Whys goes on too long, you might run out of facts, not to mention patience. The kid is onto something, though: “Why” may be one of the most powerful words in any communicator’s vocabulary.

It’s endearing at first—when you know the answers. But if the string of Whys goes on too long, you might run out of facts, not to mention patience. The kid is onto something, though: “Why” may be one of the most powerful words in any communicator’s vocabulary.

Think about it: How do you learn best? Is it by memorizing facts? By listening to someone tell you what you should think? Or is it by discovering things on your own? By turning thoughts over in your mind until you discover one that resonates for you?

So why do people insist on standing up in front of their employees and telling them about the latest reorganization or change in strategy?

Instead, try talking about the reasons behind the change. “What would you do if you saw [this situation]? Would you let it continue?” Or “How can we drive profitability more consistently? Would you try X? or Y? How about Z? We considered all of those options…”

Now, as Michael J. Marquardt points out in his book Leading with Questions, asking does require a certain openness. Would employees lose respect for a leader who openly admitted not having all the answers? I think the opposite would happen—and Marquardt agrees: Show people your true self—uncertainties and all—and they will respect you more for being authentic.

Questions also signal that you respect and value your listeners. Judith Ross quoted Marquardt in her Harvard Business Review article called “How to Ask Better Questions”:

“When the boss asks for a subordinate’s ideas, he sends the message that they are good — perhaps better than his. The individual gains confidence and becomes more competent.”

Questions: the most powerful words

Whether you use them in a speech, in a written communication, or in a personal conversation, questions can serve a number of functions. This handy list comes from the Harvard Business Review article:

- They create clarity: “Can you explain more about this situation?”

- They construct better working relations: Instead of “Did you make your sales goal?” ask, “How have sales been going?”

- They help people think analytically and critically: “What are the consequences of going this route?”

- They inspire people to reflect and see things in fresh, unpredictable ways: “Why did this work?”

- They encourage breakthrough thinking: “Can that be done in any other way?”

- They challenge assumptions: “What do you think you will lose if you start sharing responsibility for the implementation process?”

- They create ownership of solutions: “Based on your experience, what do you suggest we do here?”

Note the open-ended nature of these questions. They allow someone to answer expansively. They don’t prejudge, or put the respondent into a defensive mode. For instance, if you wanted to know why a project was behind schedule you could ask, “Why is this project behind schedule?” Or you could use the last question in that list above. “You know, our clients expect us to deliver on time. Based on your experience, what do you suggest we do here?”

Lawyers learn never to ask a question they don’t already know the answer to. That may be excellent advice in a courtroom, but Marquardt says the rest of us can let it slide.

“You don’t have to have the answer to ask a great question,” says Marquardt. “A great question will ultimately get an answer.”