Art and Gap Th_ _ ry — Song for a Sunday

I don’t mean to hit you with behavioral science first thing on a Sunday morning. We’re supposed to be talking about songs, right? My weekly “Song for a Sunday” post. But when I was prepping the material for my writing program session this week, I remembered a beautiful song and it’s the perfect illustration of Gap Theory. So here’s a song and a writing discussion for you: two blogs for the price of one.

So what is Gap Theory—or, as I like to call it, “Gap Th_ _ry”?

I wanted to Google y’all a fancy definition, but I see I need to be more specific. Apparently there’s a “gap theory” in Creationism, to explain a whole bunch of stuff God did in between the first and second verses of the Bible. Not the first and second books, mind you—verses. As in:

1 In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.

Then, according to the Gap Theory, a whole bunch of un-written-about stuff happens offstage—which is a really terrible way to tell a story, by the way—until we pick back up with:

2 The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.

To translate for anyone unfamiliar with the permutations of evangelical Christianity: A bunch of folks who claim to take the Bible literally have literally invented a whole back-story to fill in the teeny-tiny space between the period at the end of Genesis 1:1 and the capital T that starts 1:2.

That’s their Gap Theory, not mine. But—hey—I guess this post is now semi-appropriate for a Sunday. Or a Saturday, depending on whether you read your Bible left-to-right or right-to-left. But let’s get back on track.

Gap Theory and Behavioral Science

Aaah…that’s better. It turns out the “Gap Theory” that Chip Heath & Dan Heath talk about in their book Made to Stick is actually called the “Information-Gap Theory.” This theory was indeed, as the Heaths explain, articulated by George Loewenstein, a co-founder of the field of behavioral economics. (Wikipedia adds the delicious detail that his middle name is Freud.)

The Heath Brothers write that curiosity creates knowledge gaps, and

“Loewenstein argues that gaps cause pain. When we want to know something but don’t, it’s like having an itch that we need to scratch. To take away the pain, we need to fill the knowledge gap.”

So if you want a sure-fire way to capture and keep your audience’s attention, open up a knowledge gap and take your sweet time filling it.

Charles Dickens understood this in the 19th century when he published his novels in serial installments with a cliffhanger ending each one. Aaron Spelling understood this a hundred years later when he made Dallas fans hold their breath for an entire summer wondering “Who shot J.R.?”

But writers aren’t the only creators who can capitalize on their audience’s need for completion. Musicians can, too. And also visual artists, but I’ll save that for another post.

And that brings us to the song

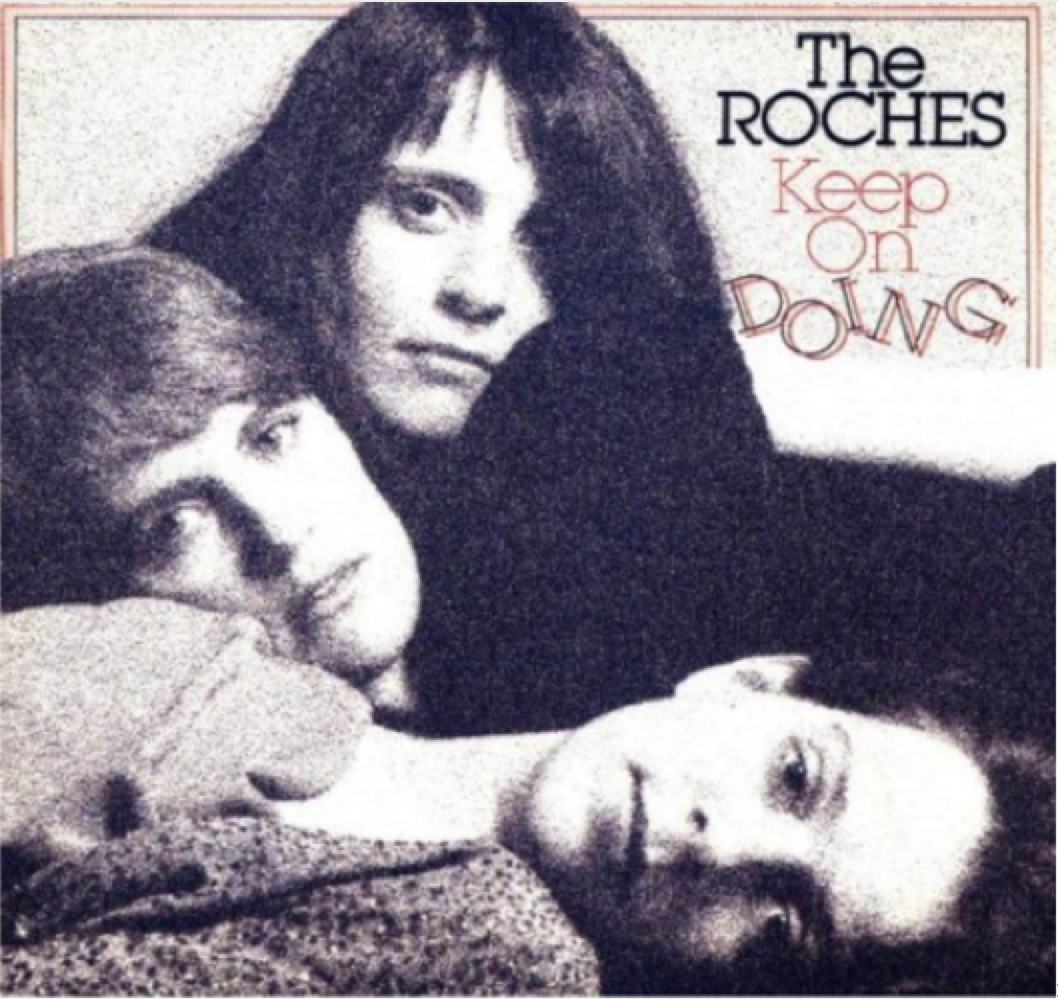

Back in the day when music only existed on record albums, I had an album I loved by The Roches, three sisters who sang tight, unexpected harmonies. And every time I listened to that album—every time—when the first side ended, I had to stop what I was doing and turn the album over to hear the second side.

This was not always as easy as it sounds, as back in the day one used to stack albums five or six deep on turntables. So I’d have to stop the music altogether, unthread the albums from the pole in the middle of the turntable, fish out The Roches’s album, turn it over, and put it on the bottom of the pile. Eventually I wised up and just kept it in permanent residence on top.

Why did I go through all that trouble? Because The Roches had opened up a gap: they ended the first side of the album with an unresolved chord.

I loved the song, “On the Road to Fairfax County,” but it also drove me crazy. And my brain couldn’t let go of the gap until I heard them properly resolve an ending.

Hear for yourselves.

By the way, the lovely lady in the green jacket, Maggie Roche, passed away earlier this year—leaving a gap no amount of knowledge can fill.