“Everything was Possible”—a Sunday song

Downsizing’s a bitch. Recently I’ve found myself needing to answer a question I thought I’d never ask:

What makes a book worth keeping?

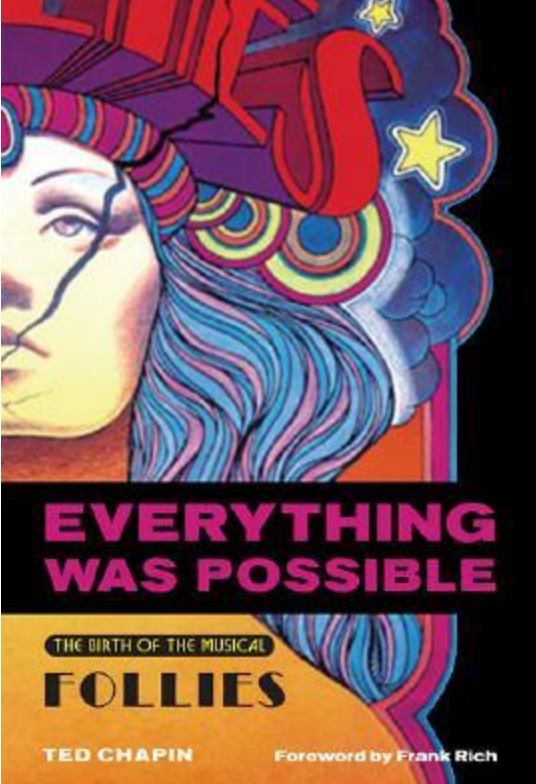

Like everyone else, I mostly read e-books now. But of course I’ve got a lifetime of book-books too. Or I did, before the first downsizing several years ago; this current purge will be even harder. But as I unpacked some of the lucky volumes onto the completely inadequate bookshelves here, I smiled when I encountered Everything was Possible by Ted Chapin.

It’s not just a compelling read about the birth of one of my favorite musicals, Stephen Sondheim’s Follies. It’s a rare window into the creative process. You Are There to see how great art gets created on a deadline.

Thousands of college kids intern in the theater. It was Chapin’s good fortune to be interning on Follies as it made its way from rehearsal room to Broadway. It is our good fortune that Chapin’s college required him to keep a journal of the experience. And what an experience!

Everything was possible

Everything was Possible may sound like a self-help book (perhaps an oddly pessimistic self-help book). But I can’t read the title without hearing the rest of the lyric

Everything was possible and nothing made sense

How often could that line describe your own life? It certainly has described mine.

I don’t remember many specific stories—I read the book a decade ago. (But you’d better believe I’ll be reading it again soon.) But one story stuck with me: Ted Chapin was only the second human being in the world to see the lyrics of Sondheim’s iconic song “I’m Still Here.” As I recall, Sondheim handed him the manuscript to type up so actress Yvonne DeCarlo could rehearse. The intern rolled a thick wad of paper into his typewriter—typing paper interspersed with carbon paper to make as many copies as possible (that’s how they did it, kid, before Xeroxes and scanners) and willed himself to be accurate, because carbon copies were impossible to correct.

I remember typing that way: you had to hit the keys with some force if you had any hope of the bottom copy being semi-legible. Of course, Chapin didn’t know in the moment that he was transcribing a timeless classic. He only knew he had to do it as quickly as possible.