The 10 Writing Commandments of Elmore Leonard

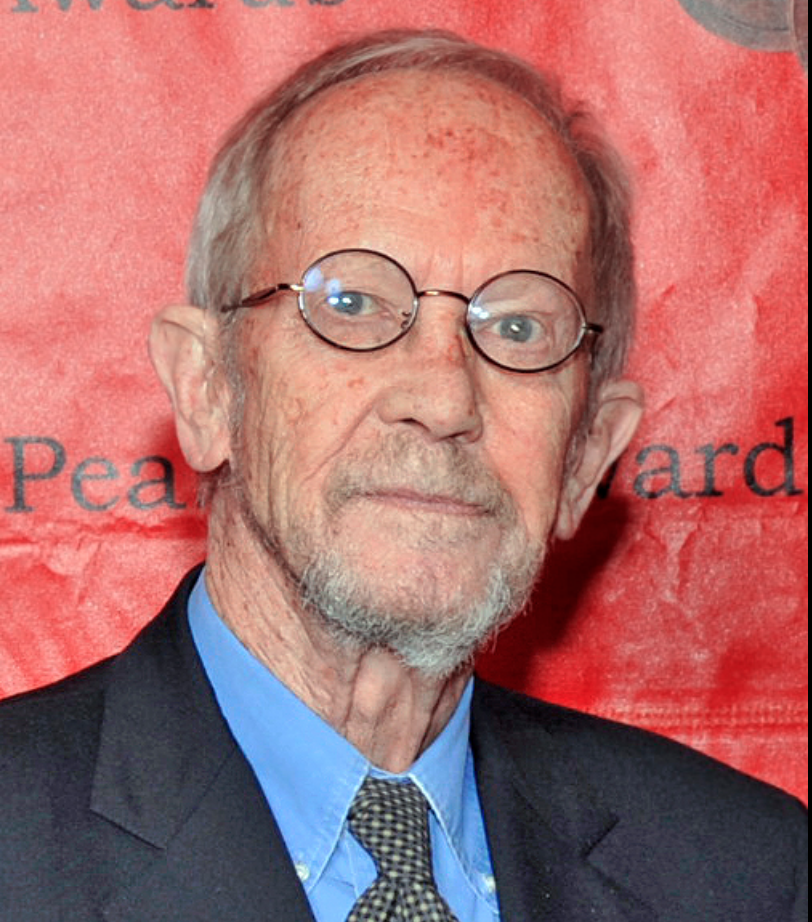

Elmore Leonard – Flickr, Creative Commons license

Writing about editing the other day, I was fishing around for that great Elmore Leonard quote—you know:

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

And I discovered it’s part of an entire article he wrote about writing in The New York Times. It’s his 10 Commandments of writing, and—spoiler alert—he calls this the “most important rule.” And so it is.

But many of the others are well worth your attention—even if you don’t write highly stylized mystery novels.

“1. Never open a book with weather.”

Now, most of my people don’t write books. But this rule works as well for speakers and writers of nonfiction as it does for novelists.

“If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people.”

Yes, even in a business context “the reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for”—if not people, then at least story. Some human connection. Give it to them as quickly as possible. In fact, start with it, weather be damned.

“2. Avoid prologues.”

Leonard warns against prologues because:

“They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword.”

Many speeches contain prologues—the endless lists of people to thank, throat-clearing about insignificant stuff: “Thanks for coming out in this rain, folks.” (See rule #1.) Get to the point.

Watch yourself some TED Talks. No prologue there. The speaker dives right into the story, and you’re riveted. Don’t you want your audience to be riveted too? Do that: dive in.

“5. Keep your exclamation points under control.”

“You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.”

Especially in business writing, there’s really no place for that level of excitement.

But my favorite piece of advice—seriously, I love this so much I may have to embroider it on a pillow:

“10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

Right? But how do you know what part that is?

Well, what parts do you skip? For me, it’s lists. Sometimes writers try to disguise a list as a paragraph. Lazy, lazy writing. If it’s so important for me to know about each of these things, then tell me why. Don’t just list a bunch of brands, for instance, and expect me to be impressed. What did you do for each of those brands? How did you leave their companies different than you found them?

Of course, Leonard is thinking about fiction:

“Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.”

“I’ll bet you don’t skip the dialogue.”

Business writers don’t often deal with dialogue. But we do tell stories. Or we should. You don’t skip the stories. You pay attention—always—when there’s an emotional connection between you and the material. So do that. Always.

And if it sounds like writing, rewrite.

Your creativity called. It wants to be taken seriously. Join us.