How to build a fan base? Think like your audience

Last weekend, Major League Baseball rolled out a new feature: Players Weekend. The players wore different uniforms, with the most hideous socks imaginable, and instead of having their last names on the backs of the jerseys, they each had nicknames.

The ostensible purpose of this exercise was to attract more young fans to the game. As a side effect, it also gave the teams a fresh batch of merchandise to sell. Okay, they’re auctioning off the game-used jerseys for charity, but MLB will happily sell you a replica for anywhere from $30 to $200.

I’m not the only person baffled by this promotion. If you’re a fan of the last Mets pitching star still in the rotation, Jacob deGrom, will you really be more likely to beg your parents to buy his jersey when it has his nickname on it rather than “deGrom”? That nickname, by the way—prepare yourself—is Jake.

The Spanish-speaking players seemed to go for more interesting monikers. Infielder José Reyes went with “La Melaza,” which apparently means “sweetness.” One of our relief pitchers, who has a Puerto Rican grandparent, was “Quarterrican.” I’m amused by the wordplay, but would a kid care?

And the night games still started at 7pm—or even 8:00—and still dragged on for more than three hours, on average. You want to attract the next generation of fans? How about playing games while they’re still awake?

No, the nickname promotion seemed to focus more on increasing MLB’s profits rather than increasing its fan base.

What could they have done differently?

To build a fan base, start with empathy

People want to feel special. Actually, more than that, they want to feel like you think they’re special.

I suppose kids named Jake might feel special to know they share a nickname with a major league pitcher. But that’s a pretty limited universe. (And a pretty unsurprising nickname.)

What if instead of offering to sell young fans something, baseball actually gave them something instead?

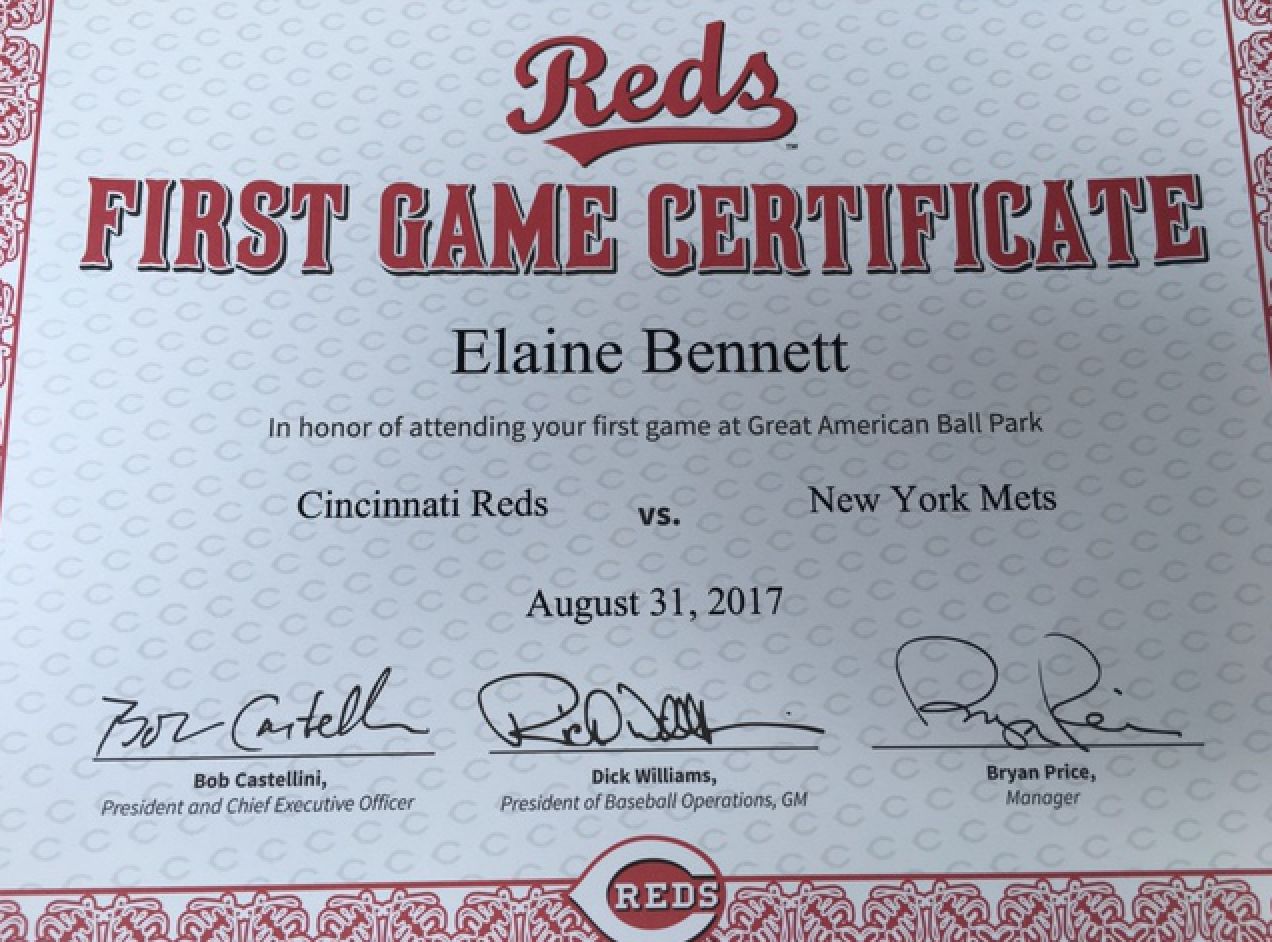

I haven’t been a “young fan” since well before the current crop of players was born, but I felt pretty darn special yesterday when the Cincinnati Reds gave me a certificate to commemorate my first Reds game.

There I was in my Mets jersey and “2015 National League Champions” cap and they still gave this to me.

Now, imagine you’re actually a young baseball fan. Does this certificate go up on your bedroom wall? I think it does. And I can’t see when it comes down. Wouldn’t you always want to remember your very first major league game?

And once you’re a member of the club—I don’t mean the ball club, I mean the club of people who go to baseball games. In this case, people who go to Reds games. Once you’re a member of that club, don’t you want to stay in it?

Now it’s true, if you’re focused on the bottom line, there’s nothing in this for the Reds. They’re not making a buck on this transaction. In fact, they’re losing money—paying an employee (today it was sweet-as-pie Rita), to sit at the computer, offer her congratulations, personalize the certificates, and print them out for the fans.

But what return is the team getting on that investment?

Young fans who feel special will grow into older fans who feel special. Catch a fan young and you’ve likely got a lifelong fan. That’s a lot of chili dogs and beer (and Graeber’s ice cream—a revelation) and merch to sell.

Somebody in the MLB marketing department ought to visit a Reds game one of these days. If it’s their first time, the folks at Fan Accommodations will be happy to give them a commemorative certificate. For free. Rita would be far too polite to say it outright, but the baseball execs might get the message: building a fan base means building a community. It’s not about getting people to buy merch, it’s about them to buy into the experience.