Ben Franklin’s sister: when women were an afterthought

Today is Benjamin Franklin’s birthday. This fact was drilled into me from a young age—long story. But let’s look past the Great Man and pay some attention instead to Ben Franklin’s sister Jane.

Today is Benjamin Franklin’s birthday. This fact was drilled into me from a young age—long story. But let’s look past the Great Man and pay some attention instead to Ben Franklin’s sister Jane.

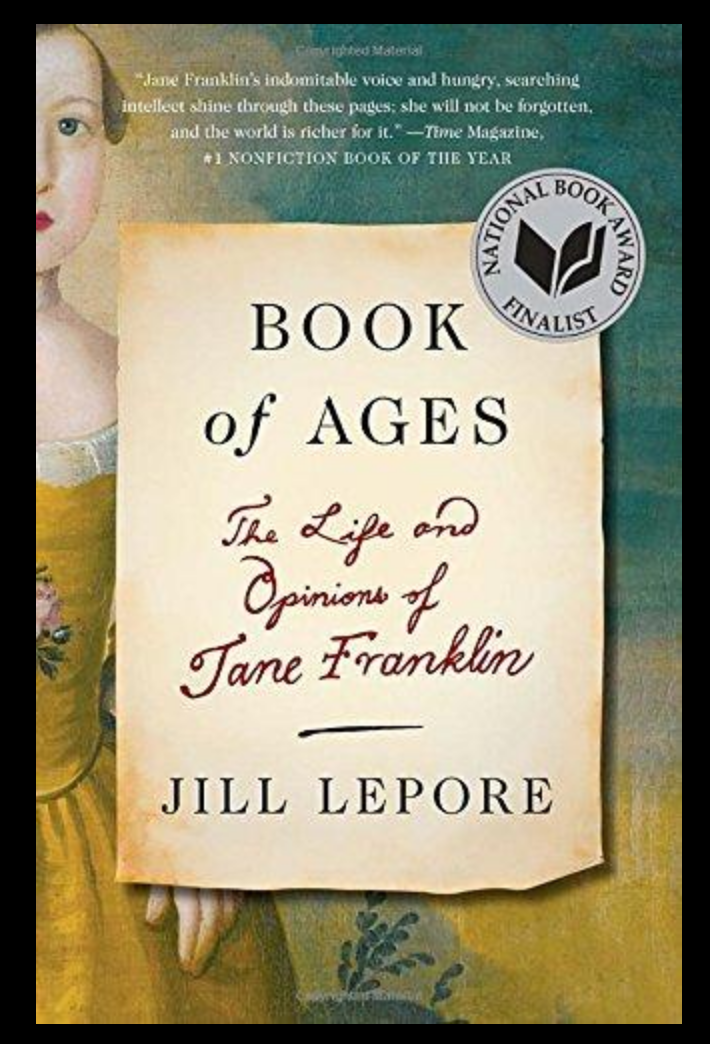

I first encountered her in the pages of The New Yorker, in an article by Jill Lepore that combined personal reminiscences of her childhood with stories of Jane Franklin Mecom, a woman all but forgotten by history. And she might have remained forgotten were it not for her relationship to one of our country’s founders.

Lepore notes:

“No two people in their family were more alike. Their lives could hardly have been more different. Boys were taught to read and write, girls to read and stitch. Three in five women in New England couldn’t even sign their names, and those who could sign usually couldn’t actually write.”

Jane owed her above-average skills to brother Ben:

“Benjamin Franklin taught himself to write with wit and force and style. His sister never learned how to spell. What she did learn, he taught her. It was a little cruel, in its kindness, because when he left the lessons ended.”

Ben ran away from home when Jane was 11; four years later, she married a man named Mecom and began the work of having and raising children. She would bear an even dozen altogether, with 11 surviving to adulthood—a far smaller brood than the one she and Ben grew up in, the two youngest children in a family of 17.

“If his life is an allegory, so is hers.”—Jill Lepore

We know remarkably little about the life of Ben Franklin’s sister. She recorded the births of her children in a “Book of Ages” and we also see her handwriting on a copy of one of Ben’s books that he gave her. Other than that, she exists only in her correspondence with her brother. Or, rather, in his correspondence with her—her letters did not survive.

As Annette Gordon-Reed wrote in an article about Lepore’s book:

“The very thing that tethered Jane and Benjamin then—their letters to one another—gives the greatest evidence of the gender-based chasm between them. Benjamin’s letters show his erudition and ease with the pen. Jane’s letters show the physical struggles of putting pen to paper and forming letters.”

What Ben Franklin’s sister has to teach us today

Jane Franklin Mecom was unusual in her time—not because she lacked education but because she had a brother, seven years older, who took care to teach her the rudiments of literacy.

How unusual would she be today? Gordon-Reed reminds us:

“Universal public education—amazingly enough, reviled in some quarters—has given girls the same educational opportunities as boys. Who knows? Had she lived today, Jane Mecom could have been a printer, scientist, revolutionary, ambassador and all around-know-it all. Her brother could still have been all these things, too.”

We take “universal public education” for granted in this country. But will we keep making the investments required to make sure it’s good education? I’m not willing to bet on it.

And certain elements around our incoming administration (dear God, I hope they’re fringe elements) seem to want to remove women from the workforce and consign us to the kitchen and bedroom again. How many generations does it take to transform a nation in which women receive more graduate degrees than men to a nation of 21st century Jane Mecoms?

That’s a question I hope we never answer.

Lepore reminds us of one of Jane’s brother’s famous quotations:

“’One Half the World does not know how the other Half lives,’” he once wrote. Jane Franklin was his other half. If his life is an allegory, so is hers.”