America divided against itself — Mark Twain’s vision

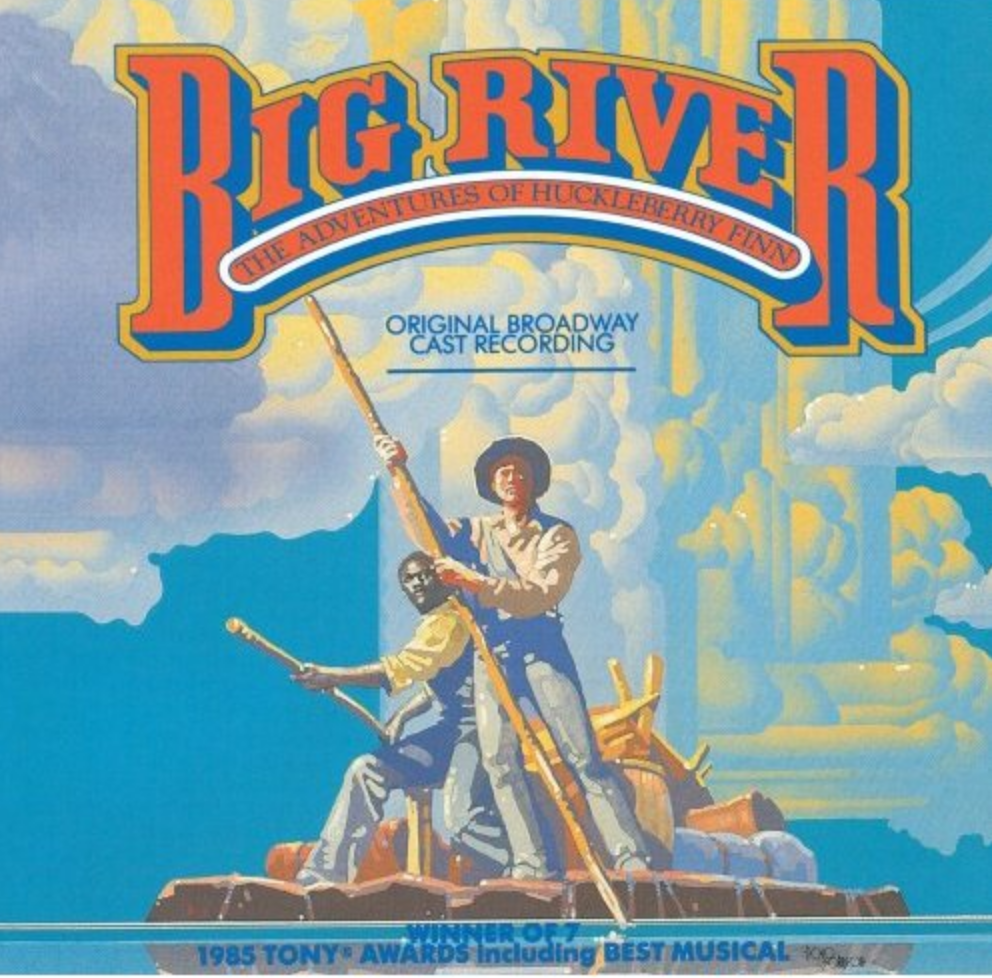

Big River’s album art, (c) Decca Records

It may seem hard to believe, but once upon a time we lived in an America divided against itself and its citizens. I revisited that time on Wednesday night, by way of a Missouri native-turned-New Englander, Mark Twain, and a good ol’ country tunesmith named Roger Williams. Yes, it was the New York City Center Encores! production of Big River.

I’d never seen the show before—and it’s been decades since I read the novel it’s based on, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. But the rollicking title song was still lodged in my brain, hammered there by the original production’s endless TV commercials. And of course I remembered the image on the poster: a white boy and a black man, floating in solidarity down the river.

Okay, in my memory they had equal weight in the graphic. I see that’s not so. But it’s a fair representation of the show, which I expect might have seemed a lot more funny in 1985 than it does today.

Huckleberry Finn: A time capsule of America divided

For those of you struggling to recall the story: Huck Finn is a scamp of a schoolboy living with two spinster ladies who try to give him some religion. In a world in which piety was not incompatible with slavery, the spinsters’ household also includes their very own enslaved person, Jim.

Huck and Jim escape separately from the spinsters’ house, run into and help each other, and embark on their rafting trip down the Mississippi. Huck is of course an ingratiating character, and the actor playing him sings and dances up a storm—he’s hard not to like. But every time we in the audience start to warm up to Huck, he calls Jim the N-word or considers giving him up to bounty hunters, or goes along with some con artists who convince him to chain Jim up, for the optics. He is indeed no angel and he knows it. Of course, he and the audience have different views about just what his misdeeds consist of: several times, Huck berates himself for being—oh yes, this is a direct quote—”a low-down, dirty Abolitionist.”

At one point, Huck returns to the raft and finds Jim chained and with a blanket over his head. Does he remove the blanket and comfort his friend? Reader, he does not. He assesses the situation and giggles with glee because Jim’s defenselessness allows Huck to play a trick on him. He disguises his voice and pretends to be a slave-hunter come to capture Jim. Naturally alarmed, Jim jumps up to defend himself, and almost attacks Huck.

Perhaps this scene provided comic relief when Twain wrote it in the 1880s. I don’t know, maybe audiences even laughed in the 1980s. But you could have heard a pin drop at City Center this week. That’s progress of a sort, I guess.

White privilege, then and now

Of course, musicals aren’t life. (Not even when they’re written by Stephen Sondheim.) But they can give us a glimpse into life. Twain’s novel—written in 1884 but set in the years before the Civil War—offers a commentary on the politics of Reconstruction in the South.

And—hey—look what I found on the website for the Mark Twain House & Museum:

“By 1877‚ neither the Republican nor Democratic Party were willing to continue their standoff concerning Reconstruction‚ and in order to secure the election of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as president‚ his party”s leadership pledged that Hayes would remove the troops and restore full state sovereignty in the South if the Democrats pledged to accept the fraudulent result of the recent election that denied Samuel Tilden‚ their party’s nominee‚ his rightful place in the White House. The deal was struck‚ and Reconstruction came to an end.”

Imagine that! Democrats rolling over—to the detriment of their supporters—after having had the presidential election stolen by Republicans. Hard to believe something like that could ever happen today.

But to my point: Neither musicals nor novels are life, but they can hold a mirror up to life. Twain dramatized the moral dilemma of people coming to understand that the law they were told to follow, the laws that would keep them on the side of Right, were themselves very wrong. When breaking the law is the only way to maintain your moral compass, well, the choice may be clear. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Big River ends with Huck’s narcissism and white privilege on full display. When he invites the newly freed Jim to accompany him on further adventures, it may sound like an interracial olive branch. But Jim looks at him quizzically. He reminds Huck of what he’d said earlier: that his first order of business on becoming free would be to raise enough money to buy the freedom for the wife and children he hadn’t seen in years. Perhaps the 1985 production played this scene differently, but at Encores I heard hurt, dismay, and resignation in Jim’s response: How could Huck have forgotten such an important detail of my humanity? Then again, how could I have expected him to remember?

It’s a time capsule America divided then—and reflection of America divided today. We don’t pay attention to the humanity of the “other”—whoever the “other” du jour may be.

We call it “white privilege” when white people ignore or minimize the challenges and experiences of people of color. Of course that’s an ironic use of the word. The privilege we should exercise is listening to each other.

So let’s climb back on Jim’s raft—together. Because we’ve still got a ways to go. Talking, listening, hanging onto our moral compass when our leaders seem to have dropped theirs in the nearest swamp. Over 130 years after Mark Twain wrote The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a lot has changed about the world. And too much remains the same.