Women or girls — a friendly reminder

I don’t remember the exact day I became a woman, but I do remember insisting—at the ripe old age of 18—on being called a woman. A few months after graduating from my all-girls’ high school, I matriculated at Smith College. And Smith was definitely a women’s college, ergo—my classmates and I suddenly realized—we were no longer girls. We were women.

As a woman I was to be taken seriously, a project that necessarily began with taking myself seriously. And so I began insisting that my bemused parents, and anyone else who misidentified me, recognize me as a woman.

Some decades later—we need not enumerate them here—I found myself calling a grown woman a “gal.” Okay, I’ll confess: I didn’t “find myself” doing this, it was pointed out to me. By the woman I had reduced to “gal” status. She was kind (she’s a friend), but firm.

She reminded me that what I’d learned as a teenager at Smith remained true: The world has enough ways of minimizing the power of women without our assistance. And referring to an adult woman as a “girl” or even “gal” (I was trying to be folksy, and we all know where that can lead) diminishes her and her accomplishments.

Language matters: Don’t call women “girls”

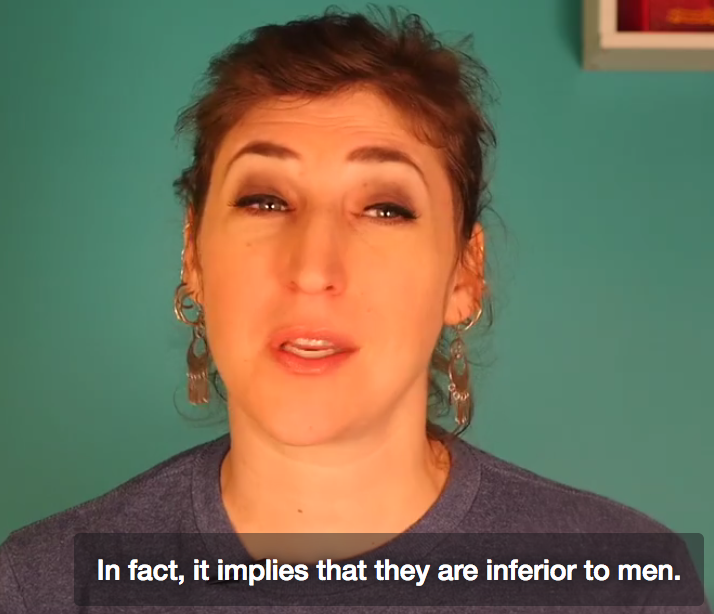

In March, actor and neuroscientist Mayim Bialik posted a Facebook video with a fantastic explanation of this. I can’t embed it, so you’ll just have to click on the link. Trust me, it’s worth four minutes of your life.

Bialik reminds us: “Language matters, words matter. And the way we use words changes the way we frame things in our minds….It’s science.”

If society sees children as inferior to adults—and it does—then calling an adult female a “girl” immediately marks her as inferior. Of course that’s not at all what I meant when I called my friend a “gal” in my blog. But it’s how people unconsciously translate the word. Even when we’re recognized as adults, women struggle to be taken as seriously as men. So we need every linguistic aid we can find to claim our status as equals.

No one should call a woman a “girl.” But it’s especially egregious when a woman does it. (Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.) If we women don’t use language that acknowledges us as full, equal members of the human race, then who will?

So hat-tip to my friend Marcia and to the fabulously forthright Mayim Bialik, Ph.D. for today’s lesson in comparative linguistics. Thanks for reminding me to be intentional with my language. This time, the lesson will stick.