The power of declarative sentences — Thanks, Mitch

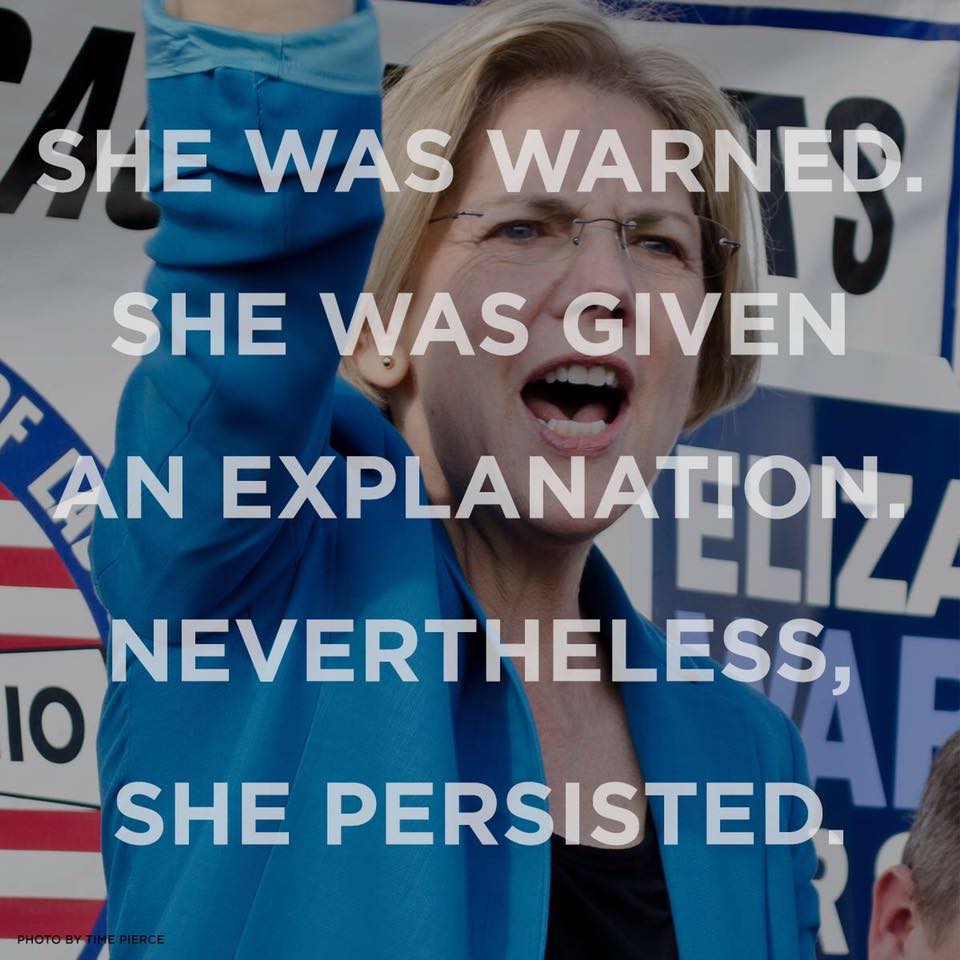

Senator Elizabeth Warren. I don’t know who to credit for the graphic.

I haven’t written about this earlier, under the principle that when your opponent is shooting himself in the foot, you don’t take away the gun. But Senator Mitch McConnell’s decision earlier this week to use declarative sentences in his denunciation of his colleague Senator Elizabeth Warren is just too delicious to pass by.

First, a definition, from EnglishGrammarRevolution.com:

“A declarative sentence (also known as a statement) makes a statement and ends with a period. It’s named appropriately because it declares or states something.”

I’m sure my current readers all know exactly what Senator McConnell “declared” or “stated” about Senator Warren. But blog posts have a long life. So for those of you reading this years from now, long after the generation of women who’ve had the last sentence tattooed on various parts of their anatomy have died out, I’ll recap.

Speaking on the Senate floor during a debate about the nomination of a Notorious Racist (and current Senator) to be our Attorney General, Senator Warren began to read a letter written three decades ago by civil rights icon Coretta Scott King. King was not impressed with the character of the notorious racist—perhaps because of his notorious racism—and she said as much. Back then, he had been nominated to be a federal judge; that nomination failed. But potato/po-tah-to: what’s disqualifyingly racist for a judge in the 1980s is apparently just the right attitude for the Attorney General in the current Republican administration.

So Senator Warren was reading this historical document into the record when she was shut down for breaking an obscure Senate rule about speaking ill of a colleague. Fun fact: the rule was apparently created back in the early 20th century to protect a senator who—incidentally—favored lynching black people when they tried to vote. I don’t know about you, but I could do with a whole lot less irony in politics today.

If you’re saying something idiotic, don’t use declarative sentences

Anyway, to the declarative sentences in question. McConnell, the Senate Majority Leader, was called upon to explain why his colleagues brought this dusty old lyncher-protecting rule out of the closet. He replied:

She was warned.

She was given an explanation.

Nevertheless, she persisted.

Politicians obfuscate all the time. They specialize in what my virtual colleague Josh Bernoff calls “weasel words”:

“an adjective, adverb, noun, or verb that indicates quantity or intensity but lacks precision.”

I’ll bet Mitch McConnell wishes he’d obfuscated the Warren explanation. Obfuscated prose doesn’t end up on tattoos or T-shirts or protest signs. “Nevertheless, she persisted” is going to hang around McConnell’s neck for a long time, like the stinking, decomposing albatross in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner“—the daily reminder of a selfish, pointless act.

Seriously, if you’re going to say something idiotic, don’t say it in the most memorable way possible. Not just one declarative sentence, but three in a row. And don’t use such a poetic cadence—short sentence building to longer sentence, building to the final sentence ending in four almost equally accented syllables: a drumbeat of declaration.

McConnell could not have offered a clearer example of how to make your message stick.

“Strict Father” says

But look at McConnell’s words again. They’re not just any declarative sentences, they’re the declarative sentences of a father chastising a misbehaving child. Why are you grounding me? That’s so unfair!!! And the father answers, “You were warned. You were given an explanation.” Okay, so I don’t know any fathers who’d find “nevertheless” tripping off their tongues. But you get the idea.

McConnell spoke that way because that’s how Conservative Republicans speak. That’s how they view the world, how they process information.

Political linguist George Lakoff has been writing about this for years—Republicans adopt the language of the strict parent; Democrats that of the nurturing parent. It’s why we don’t understand the other side’s arguments, why we can’t talk constructively.

Of course, Senator Elizabeth Warren is a fully grown adult; a Harvard Law professor; head of the panel that created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; and, since 2012, one of McConnell’s colleagues in the United States Senate. She’s also a woman, the nearest analog to Hillary Clinton left in the political arena. So they silenced her, and then offered an explanation that treated her like a miscreant child.

You might call it “dog-whistle sexism”—people who ascribe to the strict father school of government will hear the echoes of a parental rebuke in his words. They’ll absorb the message that Warren is too childish for her opinions and actions to matter.

Some might say that Warren’s silencing was driven by the Senate rules, not by sexism. If that’s the case, then why were several male senators allowed to read Coretta Scott King’s letter, in whole or in part, without interruption?

The “strict father” shtick stops working when Mother recognizes she has power and agency, too. “Nevertheless, she persisted” will help us there. In fact, it already has. Thanks, Mitch.